You probably won’t believe me, but I spent two centuries in Africa.

You may be wondering how I could be 200 years old. It does not seem possible! I did not spend the entirety of two centuries in Africa, yet my time in Africa spanned two centuries. I began my African sojourn as a Peace Corps volunteer in Morocco, and later worked in West, Southern, and East Africa as a staffer for NGOs and USAID, fighting the HIV/AIDS epidemic, malaria, and Ebola, and on famine and drought relief as well as children’s education and agricultural productivity. In my spare time, I also:

kissed a man with a knife in Morocco to protect two defenseless women.

learned how to grill sheep’s heads on the Muslim holiday.

witnessed many chickens falling from the sky in Burkino Faso.

found a lizard in my underwear (hiding in them, not wearing them).

Intrigued? You’ll have to read it to believe it!

My Two Centuries in Africa

Africa is a place of epic fights, long flights, and mosquito bites.

It all began in the Peace Corps: Morocco, 1981

-

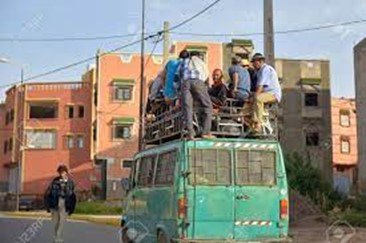

Riding the bus in Morocco

First, there was the concept of queuing - or the lack of it. In the US, if you bought a seat on a bus, it had a number, and it was yours. Not so in Morocco. People stampeded forward to buy tickets from the ticket window, then stampeded to get on the bus. The most determined people got on first, and the shyest ones got on last. A lot of little old Moroccan ladies beat us onto the bus.

Big, husky, polite American guys got elbowed aside the first few times they travelled. It wasn't that the people were mean. They didn't mean to be rude either. That's just how it was. This was just the first of many fundamental differences in perceptions and public behaviors that we would observe.

Second, there was the concept of space, and how much of it was ours, and ours alone.

At home, as a general rule, you did not get into another person's personal space. In Morocco, you didn't have any personal space around you that you could call your own. People pushed right up against you, all parts of you! You got to know people real well, real fast, and they got to know you.

The best you could hope to do was to hang onto your wallet and your backpack, and fight your way onto the bus, and into a seat. Then you would begin a long, sometimes a very long, bus ride home.

Third, let's talk about traveling with animals. Another general rule at home was, you did not bring your pets on the bus with you, and you certainly did not load them on top of the bus. If you had to bring a cat or a dog, you would carry it in a cage. In Morocco, if you had a sheep, or a goat, and you needed to take it wherever you were going, why, you just paid a little extra, and it was hauled up on top of the bus, and tied down. A chicken was small enough to ride inside.

As far as I can recall, no cows traveled on the bus, but I suspect that was only because they were too big and heavy to haul up on top. However, you could also take parts of animals with you on the bus.

I often rode next to someone who had a goat or sheep head on their lap. Why, you might ask, would a person want to carry a goat or sheep head on their lap on a bus trip? Well, they're mighty tasty, especially the cheeks, eyes, and the brains, not to mention the tongues. Say you're going to visit relatives. You don't want to show up empty-handed, so you pick up a goat head on the way.

Excerpt from “My Two Centuries”

-

Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakesh

Finally, after a series of buses, sheep, and goats, and/or their heads, I arrived in Marrakesh, and headed to my new job, at the Foyer Cheshire, at the foot of the Koutoubia Mosque. I would be working with boys who had had polio, a disease about which I knew nothing, and which had not existed in the US since it was eliminated by vaccine campaigns in the 1950s. I knew that they were crippled, but I was not prepared for what that meant. I was about to find out, the hard way.

The Cheshire Home for boys was in an old, converted dairy at the Koutoubia, the largest mosque in Marrakesh. Like many other old buildings, it was built of earthen brick, and painted in ochre.

I knocked on the heavy, studded wooden door. When it opened, out of the dimly lit entry, there was a sudden rush of bodies in my direction. Disabled boys came at me from all sides: some were upright, on crutches; others hauled themselves across the floor using their hands, while their crippled limbs trailed behind them on the cool tile floors; still others were in various kinds of wheelchairs. The boys with crippled legs tried to use their arms to pull themselves up on me so they could greet me and become my friend.

I fought back panic and the urge to scream and run away. The other Peace Corps volunteers pushed their way through the crowd to welcome me. "Don't be afraid," they said, "You'll get used to it."

After a few days, it all began to seem normal to me.

The boys used any means of ambulation that was available. Many of the boys had crutches and leg braces, and were able to walk upright, but they didn't use them all the time. They got tired and took them off and just played around on the floor. When we first arrived, we saw them as crippled children. But they were just kids, acting the way kids act.

Within a few weeks, we knew all their names and personalities: the jokers, the smart alecks, the serious ones, the athletes, the academically oriented, the sensitive and shy ones, and so on.

They called me “Aziz.”

Excerpt from “My Two Centuries”

-

Djema el Fnaa at dusk

In Djema el Fnaa, you found snake charmers, jugglers, 'Gnaoua' dancers (from Senegal) and musicians, and all manner of other curious and fascinating goings-on.

The Berber cafe was the place for cheap eats for many Peace Corps volunteers, backpackers, and other travelers. The waiters were Berbers, the indigenous people of Morocco. They were there long before the Arabs arrived. They came from up in the Atlas Mountains, where people still spoke the Berber languages. The problem was, the Berber waiters didn't speak any Arabic yet, and we didn't speak any Berber, so ordering was a hit and miss affair.

Street food in Djema el Fnaa: Freshbaked bread and steaming hot soups. It didn't matter what you ordered; the waiter would bring the first dish that was ready. It was more or less a standing joke. For a very reasonable price, we could get a bowl of "harira," the traditional, rich Moroccan soup of chickpeas and lamb, or a plate of couscous, or sheesh kebab.

After the meal, we'd have a cup, or two or three, of Moroccan tea, or sweet, spiced Moroccan coffee, mixed with varying amounts of milk.

This was before it had become commonplace for Americans to choose between latte or cappuccino or macchiato, but that was essentially the key decision we had to make after dinner every night.

After a few cups of this high-octane stuff, laced with a ton of sugar, we knew we'd never sleep a wink, but it was hard to resist. I would stay up all night and read about 200 pages of whatever book I could find, fall asleep about 4 am, and then drag myself out of bed for work at 8.

Financially, it was a tough couple of years: Peace Corps Volunteers in Marrakesh lived on $20 a day. We had a monthly stipend of $600 per month to pay for rent, food, transportation, and anything else we might need. This did not, in case anyone from the US Drug Enforcement Agency is reading this book, include illicit drugs, which everyone knows were widely and cheaply available in Morocco, like high quality marijuana or hashish.

But I digress.

Let's just say that it was enough to live on if you set your sights pretty low. We ate cheap food, and wore our blue jeans every day. Most of us walked everywhere, at least at first. Eventually, I got a used bike in one of the "souk" (local marketplace, basically a Middle East bazaar). That was my biggest single purchase as a Peace Corps volunteer, and one I was later to regret.

Excerpt from “My Two Centuries”